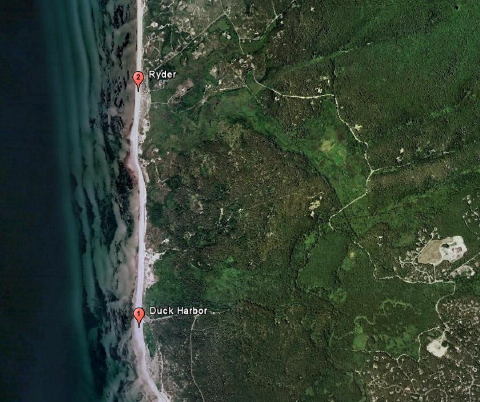

Patrolling Beach at Duck Harbor

Saturday morning of Stranding Weekend opened with a beach patrol. Participants and instructors vanned to Duck Harbor in northwest Wellfleet on Cape Cod Bay. With winds blowing north-northwest, the group trekked south from Duck Harbor to Great Island. This long peninsula protects Wellfleet Bay to the east from prevailing storms that march relentlessly west-to-east across New England. It also “catches” cold-stunned sea turtles as they are tossed by the prevailing winds onto the shoreline of Cape Cod Bay.

(NOTE:Â Click on photographs for larger images which will appear in a separate window.)

Duck Harbor in November

Duck Harbor is no more, but perhaps may rise again. Around the turn of the last century, the flow of salt water from Wellfleet Bay and the Herring River was choked by a dike in Chequessett Neck. The former islands of Griffin and Bound Brook and several others, which once were separated by salt marshes and brackish branches of the Herring River, exist now in name and memory only. The photograph above looks north toward Bound Brook “Island” with Duck “Harbor” only imagined in the darkened, low-lying vegetation where toads now emerge in spring rains. Perhaps, after decades of “planning,” the offending dike will finally be replaced. Marshes will flourish again as habitat for dwindling populations of herring and terrapins, and a critical eco-system will be restore.

What’s That in the Bay?

On reaching the beach we surveyed the coastal scene. Provincetown, distinctively emblematic with its Pilgrim Monument, rose above bay waters to our right. Invisible across the cloud covered bay lay Plymouth where Pilgrims settled after their brief stay on Outer Cape Cod. I guess the Cape had already become a “relaxing vacation spot” nearly four hundred years ago.Â

“What’s that?” exclaimed the chorus of adventurers as binoculars sprung to the ready.

What’s That on the Beach?

“What’s that?” echoed barked vocalizations from the bay, as equally curious mammals stared landward. One harbor seal, spy-hopping behind another, whispered, “Pilgrims … They’re baaack.”

Examining a Live Rock Crab

Under the storm-tossed wrack line, the place where seaweed, flotsam and jetsam accumulate with the tide, resides a museum of discoveries for the inquisitive explorer to investigate. A soft-shelled rock crab, a bit lethargic from the cold, was excavated from the wrack. Recently molted, its shell was still soft to the touch and brought out stories about steaming bushels of Chesapeake Bay blue crabs and soft-shelled crab sandwiches.

Cape Cod Bay Atlantic Rock Crab (Cancer irroratus)

We saw another specimen of the Atlantic rock crab during our afternoon cruise in Wellfleet Bay. The captain had been dragging for quahogs and brought up a lonely crab that sat atop fishing gear in the stern of the boat.

Cape Cod Bay Atlantic Rock Crab (Cancer irroratus)

After photo-documenting this obliging specimen, we returned it to the bay.

A Rock Crab in the Hand

Each field school participant enjoyed the opportunity to examine the Atlantic rock crab before we tucked it safely back under the protective wrack.

Comparison:Â Rock Crab versus Green Crab

A bit further down the beach we discovered two molted crab shells that illustrated the differences between the Atlantic rock crab and a European bio-invader, the green crab (Carcinus maenus). And, yes, it is just as “mean” as the pronunciation of its scientific name might suggest.

Checking the Wrack Line

The blanketing wrack offered a hidden encyclopedia of coastal species, and everyone joined in the act, lifting, poking and prodding eel grass piles for discoveries. As new specimens arose, instructors Sue Wieber Nourse and Dennis Murley would cite their natural history, enriched with exotic tales of lore for each species.

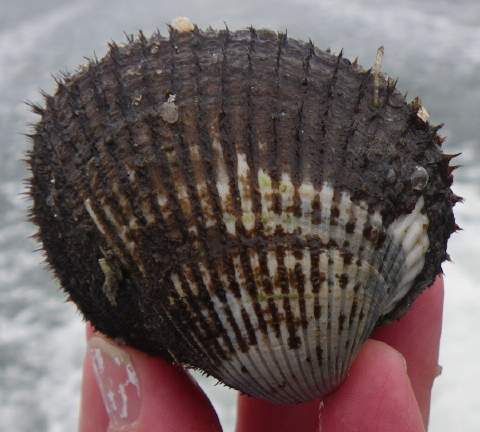

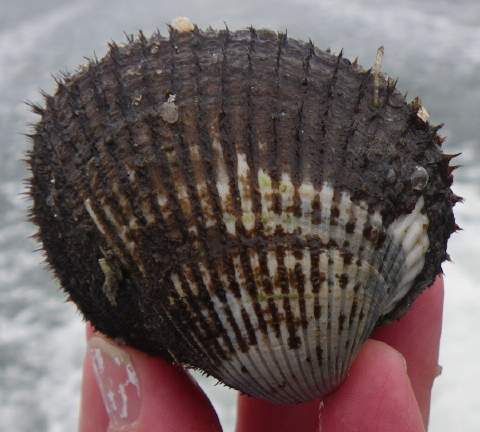

Cape Cod Bay Blood Ark (Anadara ovalis)

A blood ark appeared.  This interesting bivalve is one of the few mollusks that have red blood; hence the name. It sometimes goes by the title of Bloody Clam.

Cape Cod Bay Blood Ark (Anadara ovalis)

Ironically, when viewed from this angle, the “Blood” Ark takes on a heart shape!

Sue Wieber Nourse Explains the “Mermaid’s Purse”

Sue Wieber Nourse found “mermaid’s purses” mixed among the eel grass mat. The mermaid’s purse, also called the devil’s purse, is actually an egg casing for a skate.

Patrolling the Beach toward Great Island

And so the morning progressed. From discovery to discovery this band of intrepid adventurers explored the wind-swept beach.

Examining Decorator Worm

A decorator worm proved the next specimen. Â

Close-Up of Decorator Worm

This invertebrate critter appears to adorn itself with every tiny bit of broken shell and debris that can be found along the shore.Â

The “Eider Problem”

Dennis Murley stopped the group at one of several dead eider carcasses that we discovered along this stretch of beach. He talked about the research that was ongoing to determine the cause of these deaths, which considering the thousands upon thousands of eiders that occupy the bay at this time of the year, may be from multiple causes. Several flocks of hundreds of eiders skimmed across the wave tops as we walked the beach. Research on this matter continues.Â

Chubby Little Sanderlings

Tiny plump sanderlings worked the entire length of the beach from Duck Harbor to Great Island. They flitted along the shore a few feet in front of the group, working in the waves for morsels of food. When we approached too closely, they’d take flight and work the beach behind us.

Gulls Take Refuge Under Towering Coastal Bank

Gulls of several varieties hunkered in the protective lee of towering coastal banks. On occasion, these apparently well fed birds waddled to the water and half-heartedly poked for something munchable. For the most part, though, they seemed to enjoy the spectacle of energetic humans plodding down the beach.

Erosion Claims Coastal Development

Those towering banks on the Outer Cape always remind me of the Egyptian pyramids with their appearance of resilience and permanence. Yet, coastal banks and dunes are actually the opposite of rigid pyramids. They maintain their permanence through resilience as a soft impact barrier to the relentless onslaught of wind and sea. As Dennis noted to the group, the “angle of repose” remains constant. Sea and surf eat away at the bottom of the bank, and the top gradually falls to assume the same angle of repose as the leading edge of the bank moves slowly, constantly and inexorably inland. Resilience holds true; permanence is an illusion. And as if to underscore that point, the remnants of a coastal cottage lies destroyed in the advance of the sea and the retreat of the bank.

Erosion Exposes Deep Well Pipes of Former Cottage

Maybe a hundred feet seaward of the collapsed foundation lies the remains of well pipes that had plunged deeply into the aquifer to provide drinking water for this coastal cottage. Images serve as a clear reminder of the transitory nature of human imprint on the ever changing landscape of Outer Cape Cod. Created by the retreating Laurentide glacier 15,000 years in the past, the Cape will inevitably succumb to the advance.Â

Cleaning Up

Doing our small part to undo some of the human impact on this fragile habitat, the team collected debris as we patrolled the beach from Duck Harbor to Great Island.