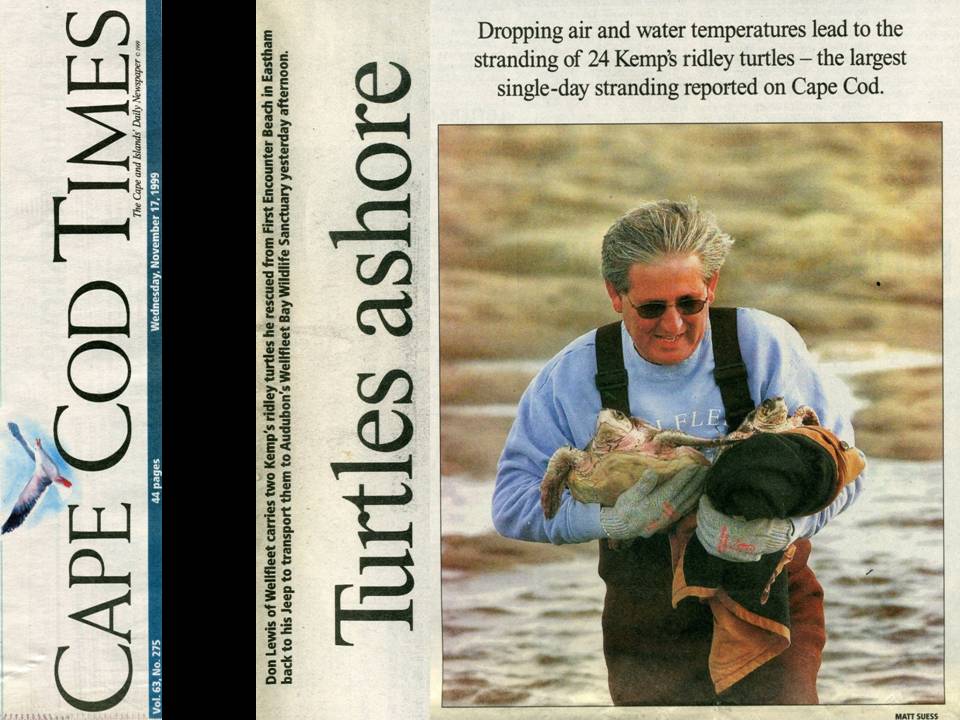

In the Great White North of Cape Cod, the sea turtle stranding season arrives each year as frost begins to form on the pumpkins. Juvenile tropical and semi-tropical sea turtles hunker in Cape Cod Bay as the season turns, water temperatures drop and they’re cued to head south to warmer climes. Unfortunately, these turtles become trapped in bay waters as the Atlantic Ocean drops more quickly to temperatures at which they cannot function. They are faced with a wall of cold ocean water and locked into Cape Cod Bay with no escape. Eventually bay water, too, reaches critical temperature and these turtles become cold-stunned and strand on bayside beaches usually beginning in early November with the lightest massed turtles (Kemp’s ridleys)  and proceeding through the season to heavier massed turtles (loggerheads) in December.

The magic temperature is 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Once that threshold is breached, sea turtles enter into stupor, gurgle to the bottom and are tossed around the bay like flotsam and jetsam. Sustained winds drive them ashore at high tide on beaches located in the opposite direction of the wind flow.

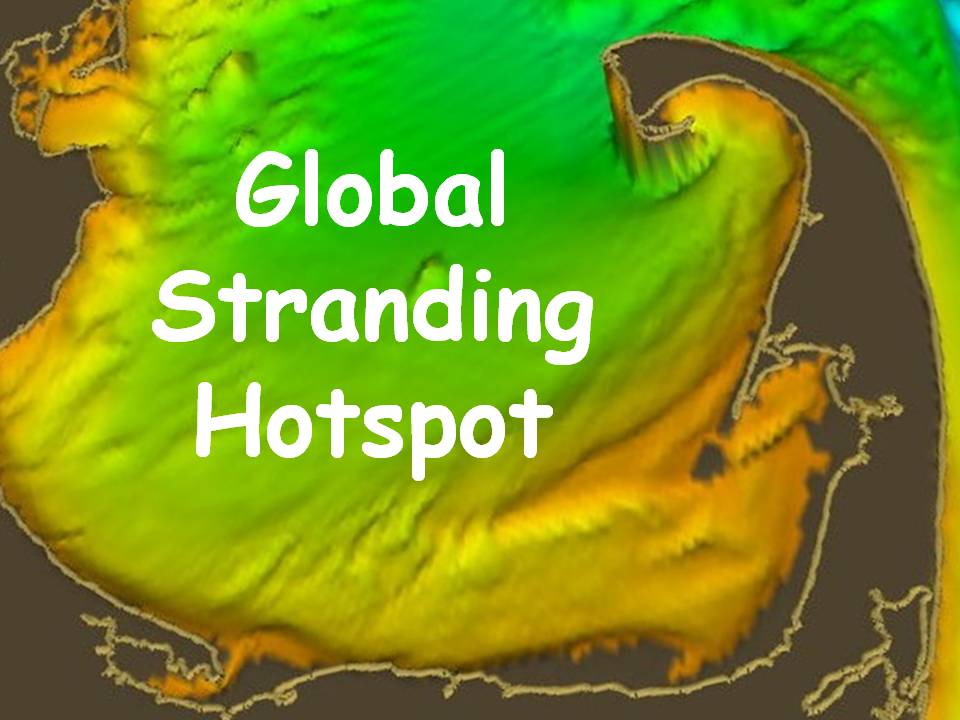

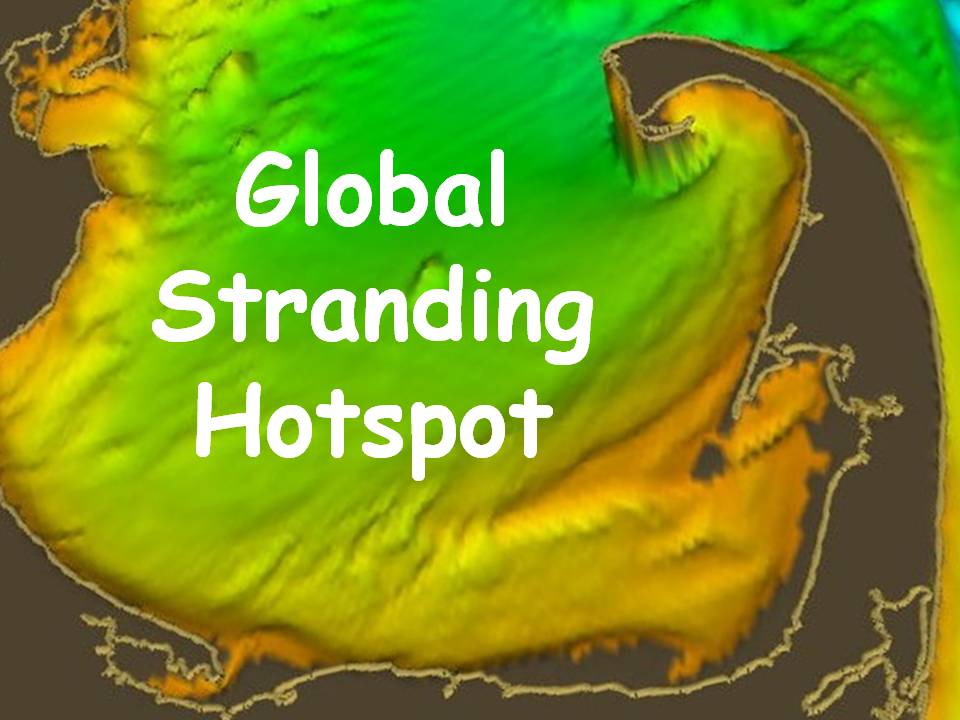

The hook of Cape Cod, an accident of the Laurentide glacier retreat, has become a huge geological trap and a global stranding hotspot for all marine animals from sea turtles to seals and marine mammals. Friday night at 7:00 pm, Turtle Journal will appear at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History in Brewster to talk about the upcoming sea turtle stranding season, about this global stranding hotspot, and about the new marine animal hospital that will open in mid-November to accommodate the rehabilitaton of stranded creatures.

The team will offer a personal retrospective of their participation in strandings of sea turtles, seals, porpoises, dolphins and small whales on Cape Cod. They will review the need for regional facilities to deal with the long, hard rehabilitative process for these endangered species, and they will highlight the new marine animal hospital which will open soon at the gateway to this global stranding hotspot in Buzzards Bay on Cape Cod Canal.

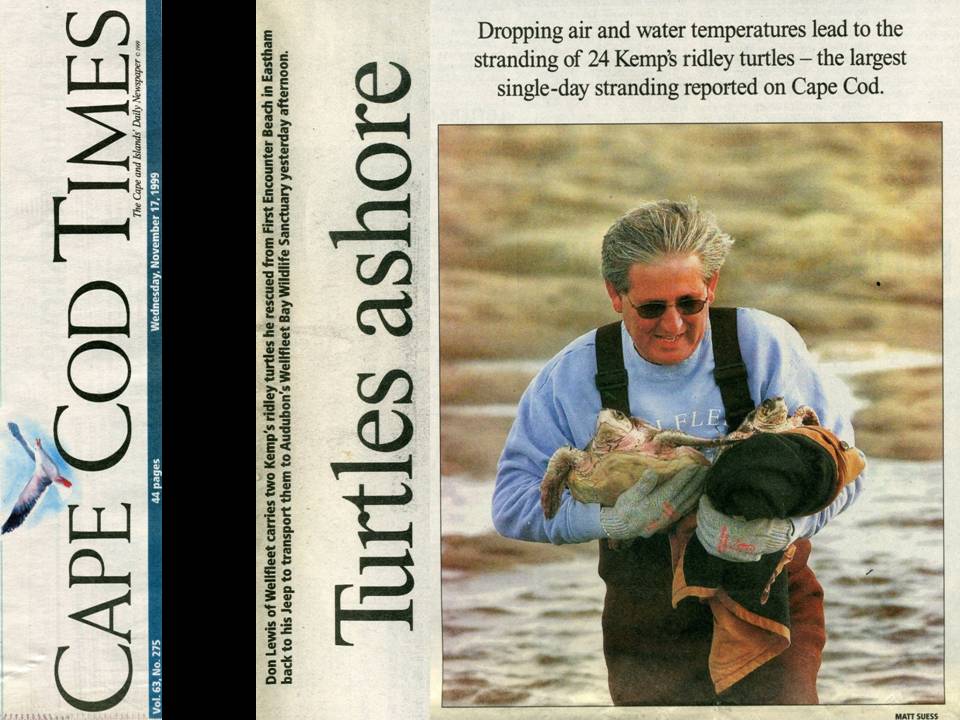

So far this fall, Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary reports one large loggerhead recovered from a South Wellfleet cove and a tiny Kemp’s ridley blown ashore in East Sandwich. Strandings will begin in earnest once water temperatures drop a few more degrees to plunge below 50 F, immediately followed by a sustained wind event for more than 24 hour duration in a consistent direction to blow them onto beaches at high tide.Â

Because these cold-stunned turtles are in complete stupor, the rules of physics rather than biology guide the progression of the stranding season. Smaller, less massive turtles are more quickly chilled and are blown ashore earlier than larger, more massive ones.Â

Intense strandings normally coincide with the first storm event of late October or early November, continue in a crescendo until mid to late November, and then gradually decrease until the end of December. Each year brings surprises, but the trend normally resembles a bell shaped curve with the peak falling in the mid to late November period.Â

The percentage of survivorship is highest at the beginning of the stranding season and drops significantly once icy slush forms along the shoreline.

Our most frequent cold-stunned sea turtles happen to be the rarest of sea turtles, the critically endangered Kemp’s ridley (top left). We usually rescue mostly two to three year old juveniles that represent 90% or more of our sea turtle strandings each year.Â

The next most frequent strander had been the loggerhead (bottom right), also juveniles in the two to five year old bracket. These animals are much more massive and tend to come ashore later in the stranding season. Over the last decade numbers of cold-stunned loggerheads have dropped precipitously, which concerns us that it may reflect a similar drop in the overall population numbers of this very America sea turtle.Â

Green sea turtles (upper right) have rivaled loggerheads lately for the second most frequent strander. They are absolutely gorgeous animals.Â

We have seen a few hybrids (lower left) in the last decade, mixtures of loggerheads, greens and hawksbills. There are only a couple of isolated hawksbill turtles that we have seen over the last few decades.

Abigail, one of our younger volunteers in the early 2000s, shows the precisely correct manner for citizens to rescue cold-stunned sea turtles that they encounter on the beach.

When you find an animal, move it above the high water line to ensure that it does not get dragged back out to sea. That would be a death sentence for these turtles.Â

Cover the animal with dry seaweed to prevent the wind from causing additional hypothermia. Do NOT remove the turtle from the beach; do NOT attempt to warm up these animals. They are protected under federal and international laws, and their successful recovery requires specific protocols and treatments.Â

Mark the pile of seaweed (under which the turtle now resides) with something gaudy that you find along the beach. There’s always something gaudy within sight and it helps rescuers locate the animal later.Â

Finally, call for pick up at the numbers listed above. When you identify the beach or landing be sure to give directions in terms of left and right (facing the water) rather than cardinal directions, which can be more confusing. Describing the distance from the landing in how long it takes to walk rather than feet, yards or fractions of a mile usually works better.

If you’d like to become a part of the rescue team that is organized by Bob Prescott at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, take a look at the PDF volunteer forms below. We always need volunteers to walk beaches, volunteers to drive turtles to medical treatment, and lots and lots and lots of towels for stabilization and triage at the sanctuary.

Volunteer Beach Patrol

Volunteer Driver

Cape Cod Global Stranding Hotspot