Juvenile Horseshoe Crab in Wellfleet Marsh

Saturday proved a glorious early April day with bright sunshine and temperature rising into the lower 50s. Turtle Journal decided to make its annual spring pilgrimage to the Indian Neck salt marsh system in Wellfleet on the Outer Cape in search of emerging juvenile horseshoe crabsÂ

Juvenile Horseshoe Crab Tracks in Marsh Channel

The Fox Island Wildlife Management Area on Indian Neck lies on the north bank of Blackfish Creek. Protected by barrier dunes, these salt marshes are extremely productive, and each year we look to this area for our first sighting of tiny juvenile horseshoe crabs rising from their winter slumber along the oozy bottom. As we examined the main salt marsh near King Phillip Road, Don spotted telltale signs of miniature horseshoe crab tracks on the channel bottom.

Don Lewis Searches Marsh Bottom for Horseshoe Crab

He photo-documented the marks and then began to solve the maze to determine where the actual critter might be. Once you make your first pass along the bottom, turbidity will obscure the search. So, you better be right the first time. You can play the game yourself. Click on the crawl mark photograph to enlarge it, and see if you can determine the most likely spot to make your first probe for the critter.

Tiny Juvenile Horseshoe Crab Netted

With a small sampling net, Don probed the bottom about two inches deep at the most likely location. Of course the net became filled with loose sand and ooze. It took several dips of the net back into the water to clear away the muck, as though panning for gold, to reveal a tiny, exquisite juvenile horseshoe crab.

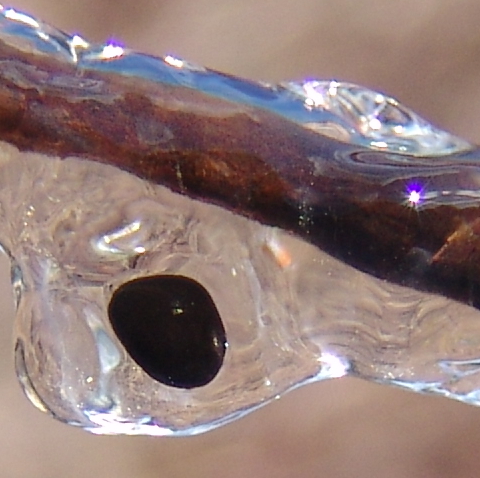

Juvenile Horseshoe Crab (Limulus polyphemus)

Juvenile horseshoe crabs are delightful to watch. Appearing as ancient as the earliest trilobites, horsehoe crabs create awe in the Turtle Journal team as we study them each year. Sadly, humans have harvested these marvelous creatures to the edge of extinction, impoverishing our entire tidal and inter-tidal eco-systems, as well as driving certain shorebirds that survive long migrations on horseshoe crab eggs to the brink, too. It gives us joy, though, to find juveniles each spring as we hope for sanity to prevail in state and federal management of this important species. As you may know, horseshoe crabs are true blue bloods (with copper rather than iron) that yield a powerful bacterial detector that saves human lives. They’re also extremely valuable in the research of vision (with both compound and simple eyes) as well as many other scientific and medical breakthroughs.

Underside of Tiny Juvenile Horseshoe Crab

Upside down, this little horseshoe crab presents a nice view of its five pairs of walking, swimming and foraging legs, as well as its book gills behind the legs. You may know that to grow, a horseshoe crab must molt.  It leaves its shell when it gets too confining, and soon a new, larger shell hardens around its soft tissue. It takes sixteen and seventeen molts respectively over a period of nine to eleven years for a male and a female to reach maturity.

Release of Juvenile Horseshoe Crab Back into Marsh

As soon as we finished our analysis of this youngster, we released it back into the same marsh channel. It took a couple of attempts to make sure that the critter was safe and sound, as it burrowed itself back under the oozy bottom to enjoy the rest of this beautiful April day. Bon chance, young horseshoe crab!