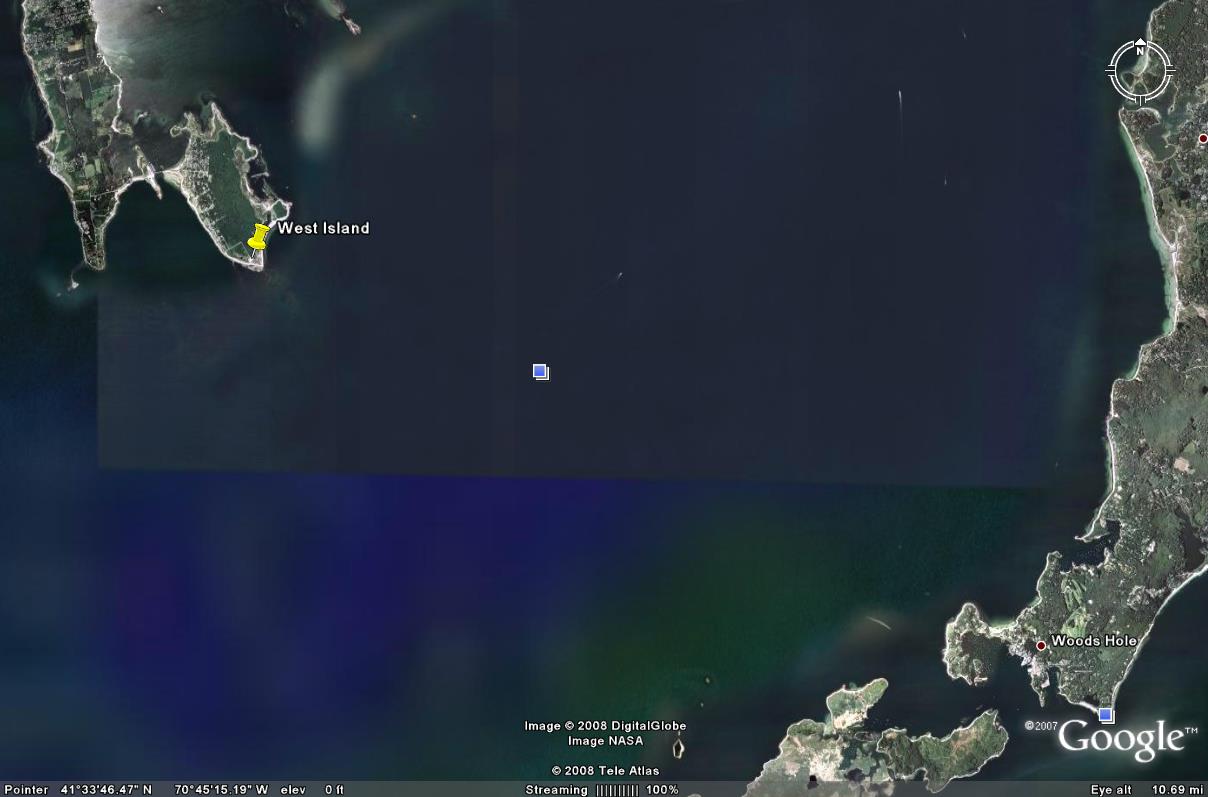

This afternoon we explored the shoreline of West Island in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. West Island lies on the western shore of Buzzards Bay across the water from Woods Hole, Falmouth and Naushon Island on the east side. The weather varied from overcast to broken sunshine with temperatures in the chilly 50s and a strong easterly breeze blowing in off the bay and ocean.

West Island on Left; Buzzards Bay in Center; Falmouth & Woods Hole on Right

West Island is not normally a specimen collector’s delight with shoreline filled inches deep and yards thick with codium and eel grass, but we chanced to arrive at dead low and we decided to explore the exposed tidal pools at the southern point of the island.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

West Island Shoreline with Heavy Codium & Eel Grass Wrack

It proved a five star afternoon: seastars, that is. We had never found seastars on West Island before, but today they seemed scattered throughout the southern tip of the island, hiding in pools of water under rocks, foraging in tidal pools and hectored by ubiquitous seagulls.

First Seastar (Asterias forbesi) on South Point of West Island

Seastars (Asterias forbesi), often popularly called starfish, have five “arms” which can regenerate. In fact, the natural history says that a seastar needs only a segment of the central disk along with one arm to regenerate into a new seastar. We should be so lucky! With mostly cloudy skies, brisk winds and chilly temperatures, seastars were moving even slower than their normal sluggish pace. But while conditions weren’t in their favor, they did present us some great opportunities to document these magnificent critters. The following sequence from our first seastar gives an overview of the creature’s dorsal (top) and ventral (bottom) sides.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Seastar under Rock; Dorsal (top) and Ventral (bottom) Views

Seastars have spiny skin and belong to the phylum echinodermata along with sea urchins and sand dollars.  The top or dorsal surface of a common seastar consists of numerous scattered spines. Each of these spines are, in-turn, surrounded by tiny jaws called pedicellariae. The pedicellariae remove sand and other debris and occasionally snag passing prey. The ventral (bottom) surface of the seastar’s arms is covered with tube feet that have suctions at the bottom of each foot.  Each tube foot works in coordination with other tube feet enabling the seastar to grasp prey or move about over various surfaces. The orange spot in the dorsal core is called the madreporite and is responsible for the movement of water into the vascular system that controls the movement of the tube feet. The clip below shows the tube feet in action as it moves a shell along one of its arms.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Seastar Tube Feet on Ventral (bottom) Side of Arms

Seastars are said to prefer clams, quahogs, oysters, et cetera as prey, but will consume snails in a pinch. Tube feet on the ventral (bottom) surface act like suction cups, securing each side of a bivalve shell while the arms pull them open. The seastar then inserts one of its two stomachs into the prey and digestion occurs inside the clam, turning the mollusk into liquid that is guided into the seastar’s mouth by cilia on its arms. The seastar sucks up the liquified clam.

Ventral Surface with Lots of Shelled Critters Moving Along Tube Feet

The second seastar we encountered had previously regenerated one of its arms which was obviously smaller than the other four. This ventral image below illustrates the size difference.

Seastar with One Regenerated Arm

More active than the first seastar we had discoverd, this one showed off its speed as it “dashed” along a shallow tidal pool. I know there are some who say that observing a sailboat race is akin to watching grass grow, but it’s clear that those folks have never invested time as spectators in the ultimate sport of champions: seastar racing. If you have time to invest, we encourage you to enjoy the next two exquisite videos, beginning with the tube-foot dash through the tidal pool.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Seastar Glides through Tidal Pool

For those who have survived the previous experience, you are well prepared for the ever-exciting seastar sport of gymnastics; that is, tumbling 180 degrees from ventral up to dorsal up. Judging is based on artistic content, plus degree of difficulty. A perfect five point landing earns the highest points, especially from the Eastern European judges who are more technically oriented.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Seastar Acrobatics

We found another seastar hugging the underside of a rock and rescued a fourth from the ravages of pestering seagulls. The fifth and last seastar we almost missed because it looked more like a butterfly lying in a shallow pool. It had lost three of its arms and we thought we had run across a goner.Â

“Butterfly” Seastar with Only Two Arms

But a closer examination revealed that this seastar had healed from its injuries and was a lively and healthy critter, perhaps proving the point that chopping up seastars only serves to create more seastars!

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Healthy Two-Armed Seastar

A surprising day for the Turtle Journal team. Temperature, wind, clouds and season conspired against us. But the gods smiled and gave us quite literally a five star day.