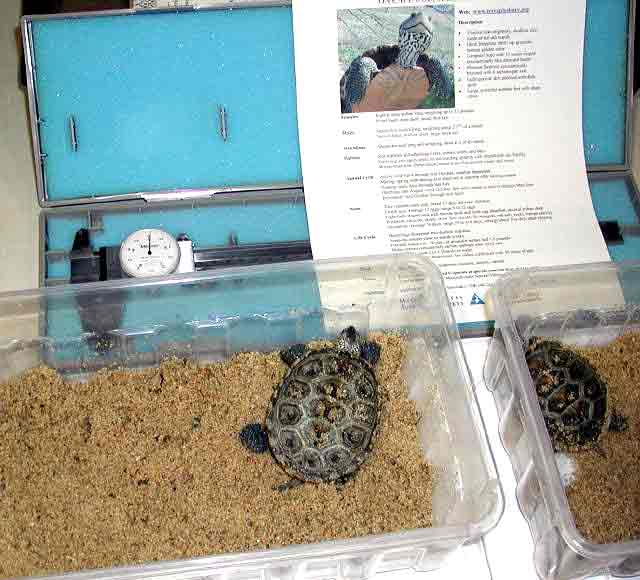

Reunion — 9 March 2003 The New England Herpetological Society invited me to present a diamondback terrapin program on 9 March at Wompatuck State Park in Hingham. To spice up a slide presentation, I asked Dr. Barbara Brennessel (right), chair of Wheaton College’s biology department, to join me with the five hatchlings she and her students have been head-starting. These babies came from a storm eroded nest. Their eggs were found exposed to the elements and relocated to a moist, sandy bucket in my garage lab. They finally emerged at the end of October as our Halloween hatchlings. Barbara kindly accepted them as part of a head-start project with her students, because the prospects of their survival so late in the season were close to nil. They have prospered under Wheaton’s care. In the first 20 weeks, they have increased their weight by nine times (for the runt) to nearly 17 times for the largest hatchling (left). And they still have another eight to ten weeks to grow before they are marked and released into their natal marsh.

Tracking these hatchlings presented us with quite a challenge, the solution of which may offer a hint at a completely safe technique to uniquely identify them. To date, we have not found a method acceptable to us for non-intrusively marking hatchlings in a way that would assure us that there would be no adverse impact on their survival once returned to the wild. We cannot, therefore, track released hatchlings into juvenile stage until their shells have become large enough and hard enough to mark safely. So, when we opted for head-starting this group, the challenge arose of devising a method of identifying each animal to plot and analyze its individual growth pattern. Based on a similar technique to her salamander project, Barbara hit upon the concept of tracking each hatchling by its unique marking patterns of its plastron. In the case of these five, each hatchling’s pattern was distinctive enough to be easily recognizable even after 20 weeks of accelerated growth. The top strip shows Hatchlings 622 through 626 digitally photographed immediately after emergence. The bottom strip documents the same five hatchlings after 20 weeks of head-start growth.

While the technique worked well for a limited sampling, whether it will prove useful in managing the identity of 600 to 700 hatchlings a year over a three-year period until they are first recaptured as juveniles is an open question. We hope to test some software programs that might enhance the possibility of tracking these design changes over time. | |||||||