Cold comfort

Cape biologists find that the best way to save injured turtles may be to put them in a chilly slumber

By ROBIN LORD

STAFF WRITER

WEST BARNSTABLE - Just like his silver screen namesake, Darth the snapping

turtle has returned for an encore appearance. Critically injured by an

encounter with a car on Stage Coach Road in Barnstable in the fall, Darth

was taken to the Cape Wildlife Center in West Barnstable, where he was the

beneficiary of a little-tested scientific theory on treating injured reptiles.

Cape Wildlife Center workers don’t usually name their patients, since they

are wild animals. But "Darth" the turtle merited a moniker because he takes

raspy breaths, just like the villainous Darth Vader in the "Star Wars" movies.

Cape Wildlife Center workers don’t usually name their patients, since they

are wild animals. But "Darth" the turtle merited a moniker because he takes

raspy breaths, just like the villainous Darth Vader in the "Star Wars" movies.

(Staff photo by VINCENT DEWITT)

|

It is simple, inexpensive and straightforward - slow the

turtle's metabolism by cooling down its environment. In a dormant state,

the turtle's body can rest and its injuries can heal a bit before the demands

of eating are placed upon it again.

After about 10 weeks, the animal is warmed up with the hope of jump-starting its appetite and accelerating the healing process.

When Wildlife Center volunteer Don Lewis lifts the dripping, mud-brown turtle

out of its travel tub on a recent day, it is obvious where the turtle got

its name. From the turtle's tapering jaws comes a drawn-out, whispered "hawwww,"

which sounds like the trademark heavy breathing of Darth Vader from the film

"Star Wars."

But the similarities between reptile and science fiction character end with

the raspy sound. No supernatural powers protected Darth when he decided to

cross Stage Coach Road last fall.

The accident left him with numerous skull fractures and a broken jaw. His

small brain case was spared, but the broken jaw prevented him from eating.

A passerby found him and brought him to the center.

Rest period Since turtles pick up on a

variety of cues from nature that tell them to slow down for the winter months,

removing Darth from his natural environment and keeping him inside the shelter

would send him mixed signals.

The warm indoor temperature would keep him active, while his instincts would be telling him to shutdown.

The warm indoor temperature would keep him active, while his instincts would be telling him to shutdown.

Wildlife Center veterinarians Rachel Blackmer and Catherine Brown were faced

with a dilemma: Darth could not eat even if he wanted to, and yet his activity

level would be taxing his injured body by using up calories.

The outlook was grim.

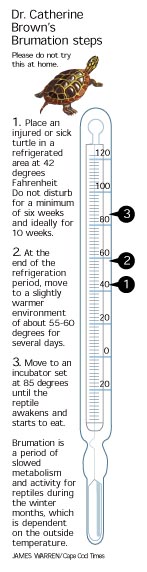

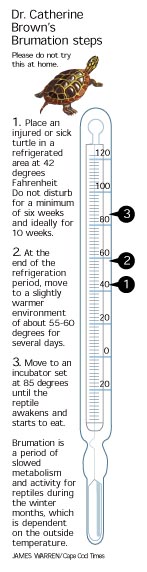

So Brown decided to test an uncommon treatment. The theory suggests that

the way to promote healing and then stimulate appetite is to force the animal

into "brumation."

Brumation is to reptiles what hibernation is to bears. It is a state of

slowed metabolism; but unlike hibernation, which lasts for a specific stretch

of time and is unaffected by temperature fluctuations, a reptile fades in

and out of brumation depending on the outside temperature.

Since there was no cold room at the Wildlife Center for a 25-pound manhole

cover-size turtle like Darth, he was sent to Lewis' house in Wellfleet. There,

in the cold, dark environment of the volunteer's garage, the turtle was left

to settle into an extended brumation.

For the next few months, he stayed underwater in a tank and occasionally rose to the surface to take a gulp of air.

The plan seemed to be working.

Turtle checkup

On a recent morning, Brown and Blackmer checked on Darth to see if he was ready to greet the world again.

Normally, the staff at the Wildlife Center, which treats more than 1,300

injured and sick wild animals each year, does not name patients. It helps

remind them they are treating wildlife and not pets.

But, because of Darth's signature greeting, "we couldn't not name him," said Lewis.

Darth is not the only turtle forced into brumation at the Wildlife Center this winter.

Brown, who has treated injured and sick wildlife for six years and has been

with the center for about six months, also tried the technique on a hatchling

box turtle and a 11/2-year-old snapping turtle. The reptiles were found weak

and dehydrated last fall and were small enough for brumation - in the center's

refrigerator.

"The winter was so up and down in terms of temperature, if they were outside,

it was not a stable brumation," she said. "The idea is to slow their activity

level and then warm them up and hope they will begin eating immediately and

heal."

The flexibility of having the controlled 42-degree setting of the refrigerator,

then warmer environs inside the center, allows the veterinarians to begin

and end brumation earlier than in the outdoors. The turtles must brumate

for a minimum of six weeks. Brown believes an optimum period is 10 weeks.

About two weeks ago, Brown decided it was time to revive the slumbering

turtles. She moved the tiny quarter-size box turtle and the half-dollar-size

snapping turtle into a slightly warmer room to gradually bring them around.

She just recently placed them in an 85-degree incubator .

Already, Brown can see improvement.

Two other injured box turtles, which were left to brumate in the dirt at

the marshside Wildlife Center, were brought inside to warmer temperatures

recently and are showing mixed results. One has responded well and is eating

vegetables and fruits, while the other has yet to eat.

Reviving Darth Darth's brumation also

ended this week when Brown and Blackmer expressed concern that his jaw was

not healing as fast as they would like. It is yet to be determined if the

brumation experiment can save his life.

"It can take years to heal these fractures. The good part is the wire we put in is still intact," said Brown.

But food is important to complete the healing process and the vets instructed Lewis to turn up the heat in his garage.

"And, you know what? If you have to feed him fingers, do it," said Brown.

Darth will eventually be fed fish, some dog food and some green matter to

entice him. In the wild, a snapping turtle of his size eats just about anything,

says Blackmer. Younger turtles tend to be more carnivorous, while older turtles

such as Darth focus more on vegetation.

The Cape Wildlife Center last year treated 46 sick or injured turtles. They

had representatives of all of Cape Cod's turtle species: eastern box, snapping,

eastern painted, diamondback terrapins, musk and spotted turtles.

The diamondback terrapin, a turtle that can live in both fresh and salt

water, is threatened in Massachusetts according to the federal Endangered

Species List. The eastern box turtle is considered a species of special concern,

which is the third most dire level on the list.

Altogether more than 1,300 animals were treated at the center last year, from bull frogs to coyotes.

Brown admits the effort to rehabilitate wildlife may be of most benefit

to humans. Wild animal populations can sustain losses and are made stronger

by the survival of the fittest.

"People who find injured or ill animals want to know there is somewhere they can bring that animal for help," she said.

But, she estimates that 70 percent of the animals brought into the center

have been negatively impacted by humans. "To a certain extent, we're helping

to make up for that," she said.

Research is also a byproduct of wildlife rehabilitation.

"Every time we handle one of these guys we learn something new about them," said Brown.

The Cape Wildlife Center on Meadow Lane in West Barnstable accepts all injured animals. They an be reached at 362-0111.

|

The warm indoor temperature would keep him active, while his instincts would be telling him to shutdown.

The warm indoor temperature would keep him active, while his instincts would be telling him to shutdown.